The Complete (And Unusual) History of Protein Powder

As the industry hits an estimated market size of $20 billion, protein powders in 2021 are everywhere, commonplace. No longer confined to bodybuilders and athletes, supplement shops and online stores, they’re stocked in supermarkets and petrol stations, marketed to senior citizens and children.

But in 1946, when US health food guru “Professor” Paul Bragg suggested that Bob Hoffman, founder of the Pennsylvania-based York Barbell Company, should expand into the nutrition business, which offered more scope for repeat purchases than weightlifting equipment did, protein powders were an alien concept; the only food product Hoffman could even think of making was protein-enriched bread.

A former US national canoeing champion turned influential strength coach and publisher, Hoffman, said Bragg, had “done what no other barbell man has”: made his students “nutrition-conscious”. But while Hoffman had recognised the importance of protein — from the Greek meaning “primary” — for building and repairing in his 1940 book Better Nutrition for the Strength and Health Seeker, he didn’t consider it any more important for weightlifters. If anything, he thought most people consumed too much protein. Compared to starches and sugars, protein was expensive, and only a limited amount could be utilised, the rest wasted. The recommended daily intake of protein was 0.02g per kg of bodyweight.

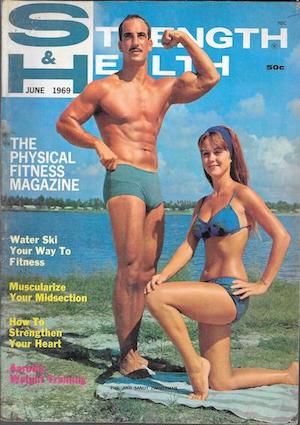

A decade later however, and Hoffman’s Strength & Health magazine were advertising something called “Johnson’s Hi-Protein Food”. Available to order via York, the supplement was “endorsed and recommended” by “famous Olympic coach” Hoffman himself.

A decade later however, and Hoffman’s Strength & Health magazine were advertising something called “Johnson’s Hi-Protein Food”. Available to order via York, the supplement was “endorsed and recommended” by “famous Olympic coach” Hoffman himself.

The Johnson in question was Irvin, who ran a Chicago health studio with gym and kitchen. In 1950, he published an article entitled “Build Bigger Biceps Faster with Food Supplements” in rival magazine Iron Man, which that year also advertised something called Kevetts “44”: the first protein powder marketed to weightlifters, containing soy beans, wheat germ and sea kelp.

The editorial pages of Iron Man meanwhile were still filled with Johnson’s nutritional inventions and the startling transformations credited to them, such as one young man who apparently gained 12lbs in 24 hours. “Mr Johnson says, ‘No one will believe this so there is no use writing it up,’” wrote Iron Man publisher Peary Rader, who didn’t share Johnson’s belief that heavy, intense training was “neither necessary nor desirable”. Otherwise Rader ate up the claims and himself gained 15lbs on the products: “Even without exercise I found my muscles becoming firmer and apparently growing somewhat.”

By 1952, Hoffman himself had entered the race, advertising ‘Bob Hoffman’s High-Protein Food’ (later changed to ‘Hi-Proteen’), in the same package size and flavour range as Johnson’s Hi-Protein Food. The eulogizing ads spoke of “a world-famous food research laboratory” where the protein was manufactured, overseen by chemists and doctors. This differed somewhat from the process later described by Hoffman’s former managing editor Jim Murray, who claimed he saw his sweating boss pour soy flour into a vat of melted Hershey’s sweet chocolate and stir it with a canoe paddle.

According to bodybuilding chronicler Randy Roach, the soy in these early protein powders was often runoff from industry that had been defatted with toxic solvents to extract the oils for paint and grease and would’ve been used as fertiliser or fed to pigs.

Hoffman boasted his products didn’t contain toxic defatted soy, but they had to be refrigerated so the unstable oils didn’t turn rancid and were notorious for causing hives and flatulence.

These stomach-churning speed bumps did little to slow the growing market though. Muscle mogul Joe Weider, instrumental in decoupling bodybuilding for aesthetics from weightlifting for strength, advertised his own “Hi-Protein Muscle Building Supplement” in a 1952 issue of Your Physique, one of his stable of magazines, six months after the appearance of Hoffman’s product. Weider’s Hi-Protein was, said the advertisements, “recommended by medical doctors”, with pictures of physicians, an official-looking certificate and a seal. The “Weider Research Clinic” referenced therein, according to 1966 Mr America Bob Gadja, was a door at Weider’s offices that led to a broom closet.

Weider’s wasn’t the first protein powder to boast medical credentials. Described in promotional materials as “the albumen of pure fresh milk in the form of a dry, soluble granulated, cream-white powder”, Plasmon had, according to a 1900 edition of British medical journal The Lancet, been used to build up hospital patients in Germany. There, Dr CR Virchow, son of prominent 19th century physician Rudolf, had enumerated Plasmon’s virtues to the German government: cheap, digestible, hygienic, and superior to meat for strength, endurance and vitality. Dr Virchow had ran trials in which, he said, men had subsisted for several days of hard work and reduced sleep on Plasmon alone.

The British entrepreneurs who in 1899 acquired the rights to sell Plasmon outside Germany and Russia marketed the product to a wider, more able audience with the help of key influencers. Plasmon “justified all that is claimed for it”, said England footballer and cricketer CB Fry, who ran advertisements and testimonials in his own publication, Fry’s Magazine. Explorer Ernest Shackleton supposedly packed Plasmon for his expeditions. “Plasmon is the very essential food I have long wished for, and I would never be without it,” said Eugene Sandow, the “father of bodybuilding” after whom the Mr Olympia trophy is christened.

Variously marketed to women (conspicuously without the logo of a flexed bicep), children (how else to develop the bones and muscles that make “red-blooded” men) and “brain workers” (desk jockeys), Plasmon tapped into contemporary concerns: food purity, productivity, a volatile jobs market, sedentarism and a perceived crisis of masculinity. This early success wasn’t to last though. In 1916 following the outbreak of WWI and hostilities in Britain towards all things German; Plasmon repatriated to Italy where it manufactures infant formula and other baby food products.

Powdered milk, eggs and soy were produced at vast scale during WWII, but protein powders per se didn’t get bigger until bodybuilding itself did, thanks to better nutrition and, in no small part, another “supplement”. At the 1954 World Weightlifting Championships in Vienna, Hoffman’s Hi-Proteen-powered US team were beaten by the USSR whose secret, a Soviet team doctor disclosed to his American counterpart after a few drinks, was testosterone: nature’s own anabolic steroid, synthesised in 1935 in Nazi Germany.

There followed hundreds of synthetic analogues of testosterone such as methandrostenolone, synthesised in 1955 in Switzerland and sold from 1958 as Dianobol in the US, where it was quickly picked up by weightlifters and other athletes. As steroids proliferated but stayed under the radar, the gains made in large part thanks to them were, ignorantly or knowingly, attributed to protein powders, which grew as a result.

Hoffman’s former managing editor Murray wanted to write an article for Rader’s Iron Man questioning the effectiveness and expensiveness of protein powders and other food supplements and accused Weider, whose publications had previously poked holes in Hoffman and Johnson’s claims, of also succumbing to “the lure of easy money”. But Rader, who’d already launched his own “Super Protein” product, didn’t bite and, with Hoffman and Weider, muscled out Johnson.

Changing his name to Rheo Blair, Johnson moved to Los Angeles, where he developed a blend of milk and eggs that he claimed came from animals raised on the rich soil of Wisconsin, with the proteins extracted at a lower temperature, followed by a formula he claimed was similar to breast milk. Blair’s products, which he stipulated should be taken with raw cream or half-and-half (a mix of cream and milk), were ‘perceived’ to be a sizeable upgrade on soy-based offerings and were reportedly used by Weider ambassadors Arnold Schwarzenegger and Lou Ferrigno – who, of course, also used steroids. (According to Roach, “Blair knew his guys were taking steroids”.)

Schwarzenegger’s star power transformed bodybuilding from niche subculture into a mainstream pursuit; even more protein powders — and steroids — followed. Created by Dr A Scott Connelly, an anaesthesiologist, Met-Rx was endorsed by athletes and celebrities: Clint Eastwood, Cindy Crawford, Cher. Met-RX, said the advertisements, could build muscle, burn fat and boost stamina, while Dr Connelly had graduated from Harvard Medical School and been on the faculty at Stanford Medical School. In fact, he’d been a post-grad special student at the former and an unpaid clinical instructor at the latter, where, he said, he’d wondered what Met-Rx, which he’d created for hospital patients, might do for healthy people and gave it to some athletes.

One of them gave it to Bill Phillips who, before launching his 12-week Body-for-Life transformation challenge and bestselling series of books, or training Sylvester Stallone for Cliffhanger or Demi Moore for GI Jane, was a bodybuilder and steroid user. Phillips promoted Met-Rx in his bodybuilding magazine Muscle Media 2000 while also functioning as, in Connelly’s words, the supplement’s “de facto distributor”.

Muscle Media 2000 also promoted EAS, which in 1993 became the first supplement brand to market creatine. Phillips eventually bought EAS, which along with its competitors benefited from 1994 US legislation that allowed supplements, as long as they didn’t contain approved drugs or claim to treat disease, to be sold without Food and Drug Administration approval or proof of effectiveness or safety, as opposed to more heavily regulated pharmaceuticals. (The legislation was lobbied for by a senator from Utah, home to a profitable supplement manufacturing industry.) To stand out in the crowding market, supplement brands would pay a commission or “spiff” to salespeople in health stores of anywhere from 25 cents to $8 a tub, and fund their own scientific studies.

By this point whey protein was the dominant force in the market. Separating milk into its constituents of whey and casein had been possible since Plasmon, but it wasn’t until nearly half a century later, when American cheese makers were restricted on dumping the unwanted byproduct in rivers and sewage systems, that whey began to dominate. Initially, these whey powders were only fit to feed to pigs, but they became more palatable to humans from the 1970s with advancements in filtration techniques — effectively sieving to varying degrees of fineness.

Over the 2000s and 2010s, supplement brands Optimum Nutrition, BSN, Isopure and SlimFast, plus Dutch multi-brand retailer Body&Fit, were purchased by the global cheesemaking giant formerly called Avonmore Waterford Group, which had rebranded as Glanbia, from the Gaelic for “pure food”.

While whey still leads, there has been a shift towards plant-based protein powders in the past decade, driven by environmental and health concerns over animal sources. Increasingly conscious consumers want to be confident of ingredient quality and provenance, to see bona fide certification of organic or vegan status. And with good reason: a 2004 study funded by the International Olympic Committee of 634 supplements from 13 countries found 15 per cent – all from the USA, UK, Germany, Italy and the Netherlands – contained steroids and other substances that would likely cause an athlete to fail a drugs test.

A further shift has been seen in how protein powder is being used. Popularised for endurance and recovery by diverse, demanding fitness trends, from marathons to obstacle races, HIIT to CrossFit, protein powders aren’t solely about bodybuilding and muscle growth anymore, and appeal not just to men but also women, participating as they do more equally in resistance training.

Protein powders have also broken out of the sports nutrition category into the realms of weight management and general healthy lifestyle. And while arguments continue to rage over the optimal daily intake of protein — a lot more than that early prediction of 0.02g per kg of bodyweight that’s for sure — what has become clear in the century since the birth of protein supplements is the importance of the nutrient for everyone’s satiety, immunity, and general health, whether you’re a hospital patient, a bodybuilder, or just a senior citizen doing the weekly supermarket run.