Workout With Form | Terroll Lewis

It’s one week before Brixton’s Street Gym’s grand reopening when founder Terroll Lewis and I meet. Nestled between gentrified Brixton Village and a mass of south London housing estates, the new site stands just a few doors down from where it previously stood, now in its final stages of construction.

It was after serving 11 months in Belmarsh Prison at the age of 19 when Lewis became committed to changing his path, and that manifested through fitness. Stuck behind bars, his cell became his gym, and he worked out around the clock to make the time pass faster. When he was released, he kept his cell routine alive at a local children’s playground.

Then, when he began uploading workouts to YouTube, people joined him, doing pull-ups on abandoned swing sets and handstands on staircases. He initially called his regime Block Workout, commandeered a disused industrial space, and membership thrived.

Setting the Bar

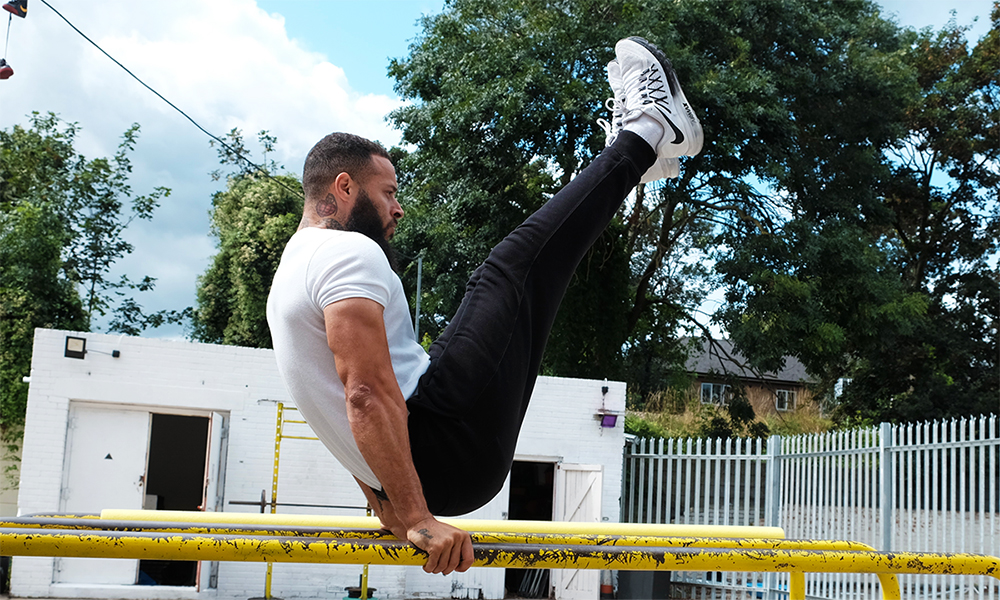

“We’ve got showers now!” Lewis beams. Hot water is high on his list of the most exciting things about his new site, provided by Lambeth Council. He takes me around the building. Inside, a torrent of LED lights are being fitted in a dedicated studio space and flooring being laid. We pass a reception area, kitchen, his beloved shower rooms and a library stacked floor-to-ceiling with books before heading outside to commence our workout on an arrangement of bright yellow callisthenics bars.

Five dips, five pull-ups, five push-ups. Then four of each, down to one. No rests.

“Wh-” I’m promptly reminded that we still have to work back up to five before I can start questioning.

What was your attitude to fitness like before you went to prison?

“I… had a fast metabolism,” he laughs. Which is to say that though he was athletic and trialled for football clubs including Stevenage and West Ham, aesthetically-speaking he was far from the muscular gymnast he is today. Regardless, aesthetics were never something that motivated him.

“Fitness became therapy for me. It started with time – I wanted time to go fast and they say it flies when you’re having fun. I was in a cell doing dips off the toilet seat, press-ups off the sink, and I grew to love the repetition of it all. The transformation wasn’t just in my physical strength, you could see a positive change in my character.”

Growing up on Brixton’s Myatt’s Field estate, Lewis found it hard to dissociate from gangs and the violence associated with them. In Brixton’s Street Gym, he provides a space that deters at-risk young people from making the same mistakes he did. The method has been tried and tested.

Bodyweight and Soul

Finding a space to channel his new-found fondness of fitness when he was released from prison wasn’t easy. Perplexed by the requirement of setting up a Fitness First direct debit (“I was so confused. I was coming off the streets – I used to keep my money under my bed”), he made the playgrounds of Brixton’s estates his training ground.

The evolution to Brixton’s Street Gym is so much more than just a place to sweat, though. The whole enterprise seems to have been set up as a mischief-prevention centre, using Lewis’ adolescent self as its model customer. Sure, there are dance classes and spin bikes; a prospective partnership with Carlson Gracie Brazilian jiu-jitsu clubs and a roster of PTs at their doorstep, but there’s also a library, CV writing and interview skills workshops.

As we take to the ground for a series of some of Lewis’ favourite push-up variations, I ask him if he sees a lot of himself in the people who come here.

“It’s not about the name or fame, estates just need stuff like this. We have to be able to put something else in their hands”

“100 per cent,” he says. “I wish there was a place like this when I was growing up. The situation I found myself in is the reason we have to do this. It’s not about the name or fame, estates just need stuff like this. We have to be able to put something else in their hands; it’s not as simple as taking the drugs away, you have to be able to support them and show them ‘you don’t need to do that because you can do this.”

The claps between our push-ups add impact to his words. In a landscape continually prioritising empowerment for the whole self, Brixton’s Street Gym is more than embodying wellbeing as more than just a place to build mirror muscles. Best of all, it’s doing it for the people who need it most. The space will even house workshops from Lewis’ other social enterprise, The Man Talk, which offers a safe space for men to have discussions about anxiety, depression, finance, relationships and other everyday pressures contributing to rising male mental health issues.

Growth Strategy

Yes, intentions and execution are inspiring, but in a part of London associated as much now (if not more) with oat milk flat whites as its gangland rep, how does gentrification affect this project?

“When a wave comes, you either learn how to surf it or you drown,” says Lewis, now initiating a dead hang from the taller bars. “Gentrification has come, sure, but it’s business too. It’s not like we’ve been kicked out – we’ve got a foot in the hood and we can still connect with the young professionals and the coffee shops. You have to use change for good.”

“That being said,” he continues as my attempt at the hold comes to an abrupt end (Lewis, meanwhile, continues one-handed). “Gentrification in Brixton is quite high street-centric. Shootings and stabbings still happen here. Stuff like this gets ignored when all you hear about is Pop and Brixton Village.”

With his free hand, he points towards a block a stones-throw from the gym, where he tells me a young boy was killed just a few weeks prior due to postcode wars.

Finally succumbing to gravity, Lewis disembarks the bars and we end our workout. Lewis tends to a decorator who has been quietly painting the exterior of Brixton’s Street Gym a vibrant yellow while we’ve been chatting. I leave wondering if it’s a colour we’ll soon see replicated near the estates of Tower Hamlets, Hackney, Birmingham or beyond. Here’s hoping.