Can Muscle Memory Help You To Regain Your Pre-Lockdown Gains?

Another lockdown and further time away from our beloved gym means yet more worrisome times for regular gym-goers. Most have resorted to building makeshift gyms in their living rooms, kettlebells, and resistance bands strewn across the carpet like a bodybuilders convention after-party. Others, like myself, have just let lockdown do its worst, slowly watching all muscle definition eek away as they spend another day making the draining bed-to-desk-to-couch-to-bed commute.

The great fear for all concerned parties is that years of dedication in the gym, and the muscles to show for it, are now slowly slipping away. Well, let us allay your concerns somewhat and introduce you to the concept of ‘muscle memory’.

In scientific terms, muscle memory refers to motor learning, a phenomenon in which practising a physical activity over and over leads to changes in our nervous system that see the action stick. Never forgetting how to ride a bike say, or Cristiano Ronaldo’s ability to scream a shot into the top right-hand corner.

In bodybuilding forums though, muscle memory is more readily associated with the body’s ability to regain strength and muscle easily after losing it. That’s what we all want, right? Well, let’s take a look behind the curtain.

Is Muscle Memory Real?

We might start with the hypothesis that once muscle is built, it never really goes away. A great deal of research has found that training a muscle increases the cross-sectional area of muscle fibres and changes the ratio of fibre types within the muscle. In other words, gains are made.

However, studies have found that even though strength quickly returns after a detraining and retraining phase, muscle fibre regrowth, once it is lost, takes longer to catch up.

We could then say that perhaps our genetic code has been altered; bodybuilder’s DNA if you will. Well, a 2016 study from the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm did investigate the effects of muscular training on genetic expression and found that the effect was sizeable.

Unfortunately, when the subjects were tested again having gone without exercise for nine months, none of the exercise-induced genetic changes were still active. The muscle memory solution must lie elsewhere.

Could Myonuclei Hold The Key?

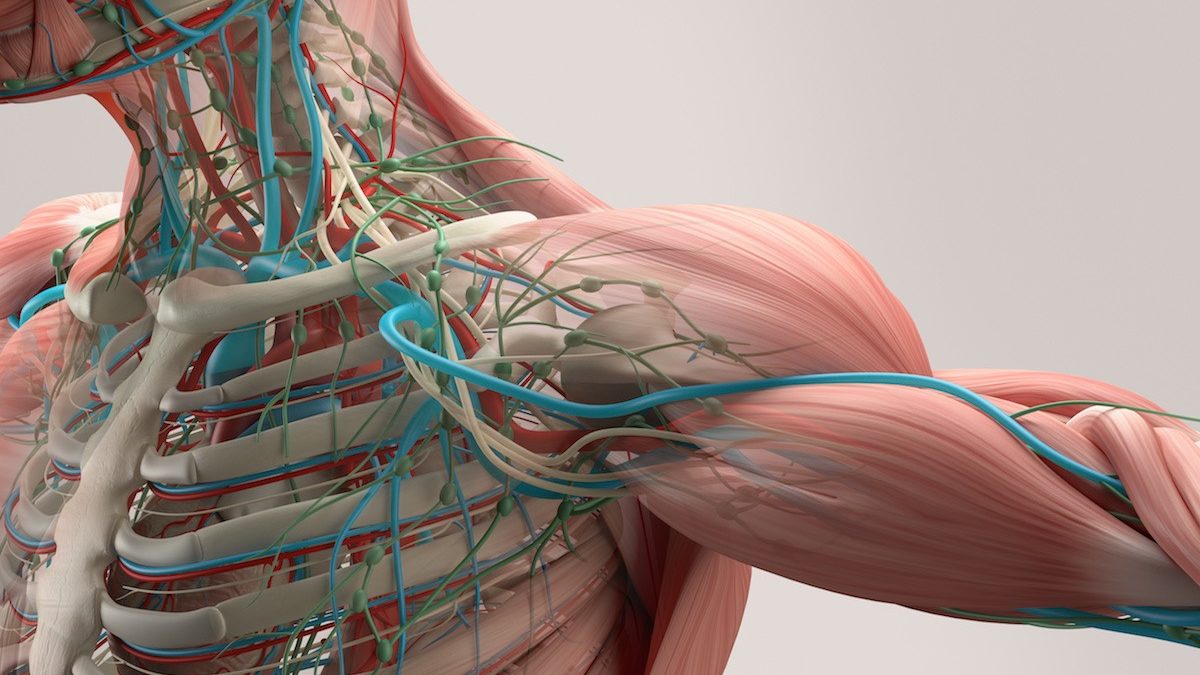

Myonuclei; you might not be able to pronounce it, but this mouthful is why you could find it easier to regain muscle mass when you hop back into the gym. Basically, each muscle cell in your body contains hundreds, if not thousands, of small nuclei (aka myonuclei) which act as control centres for the muscle fibres, and allow for the growth and repair of those fibres.

The bigger a muscle fibre is, the more myonuclei it needs to develop to support and manage itself properly. So if you’re a regular lifter you’ll probably have a lot.

Significant research over the past decade has put away previously held beliefs that myonuclei numbers changed with muscle growth or shrinkage (aka myonuclear domain hypothesis).

Two independent models, one from rodents and the other from insects, have demonstrated that nuclei are not lost from skeletal muscle fibres when they undergo either atrophy or cell death. These and other data argue against the current interpretation of the myonuclear domain hypothesis and suggest that once a nucleus has been acquired by a muscle fibre it persists.

The Myonuclei Plot Thickens

The riddle has been solved then? Not quite. A 2020 study from the University of Leuven (the most recent on the subject), measured knee extension strength and power in 30 older men and 10 controls before and after 12 weeks of resistance training, and after detraining and retraining of a similar length.

Any gained strength and fibre type changes were pretty much preserved following 12 weeks of detraining, allowing for a fast recovery of performance following retraining. Surely music to locked-down weightlifter’s ears.

However, the number of myonuclei tended to follow individual changes in type II fibre size (fast-twitch muscle fibres that support quick, powerful movements such as sprinting or weightlifting), which upholds previous beliefs that myonuclei were lost in atrophy. The report concludes by saying:

“We propose that myonuclei might be retained during rapid forms of atrophy, but that in the long-term, the myonuclear domain is restored to its untrained steady-state.” Basically, a little downtime is okay (say a lockdown’s worth) but taking a year to return to your heavy lifting regimen is likely to count against you.

Neural Adaptation

While the myonuclei argument remains up in the air, one part of the muscle memory conundrum seems to be more conclusive: neural adaptation, the change in neuronal responses due to preceding stimulation of the cell.

In the context of resistance training, neural adaptation basically refers to changes that allow your muscles to fire more efficiently next time you use them, and exert as close to the optimum force as possible.

While myonuclei allow you to quickly regain the muscle you lost, the idea is that neural adaptation instead works by pushing that muscle to work harder and better, helping you bring back strength more quickly after long periods of inactivity.

A study from the Institute of Sports Medicine in Copenhagen measured concentric (movements that shorten your muscles i.e. bicep curl) and eccentric (movements that lengthen your muscles i.e. lowering the dumbbell after the curl) force in 13 young sedentary males after three months of heavy resistance training, and three months without.

Following training, moment of force increased during both eccentric and concentric. After the three months of detraining maximal muscle strength remained preserved during eccentric contraction but not concentric contraction.

“The present findings suggest that heavy resistance training induces long-lasting strength gains and neural adaptations during maximal eccentric muscle contraction in previously untrained subjects,” said the study’s authors. This pays credence to the PT gospel that a focus on form, steady movement, and a full range of motion is the key to long-term gains.

Some Concluding Points On Muscle Memory

The majority of these studies are undertaken on men, so it’s unclear whether the biological differences between sexes play a substantial part. One study on six women found that during 32 weeks of detraining, a group of women lost a considerable part of the extra strength obtained by 20 weeks of previous training but regained the strength after only six weeks of retraining. While this is an extremely small study, it does hint towards the time frames we’re looking at for regaining muscle.

And keeping things positive, most studies on detraining do show a similar speed and ease when recovering gains lost through detraining, even if it’s not completely clear how or why.

If we’re to focus on the nuclear adaptation argument, the main takeaway is to concentrate on maintaining proper form throughout your workout, whether that be in the gym or at home. It’s a common-sense argument; if you knew what you’re doing around the gym before, you’ll see easier gains upon your return to it.