Cycling Legend David Millar on Nutrition and How It Has Changed the Sport

My career bridged the old and new eras of professional cycling; when I turned professional in 1997 not much had changed in decades, although obviously at the time we thought we were all terribly modern.

There was a deeply embedded doping culture and with that came a medical system that was based on injectable supplements. Natural was not a done thing. The word nutrient wasn’t even part of the lexicon. It was all about recuperation through pharmaceutical products.

Food was fuel in the most basic sense: carbs for speed, protein for strength, both for endurance. Teams didn’t even consult or employ chefs or nutritionists.

Nutrition In Cycling

By my final year racing, 2014, everything had changed. There was an anti-doping culture within professional cycling. The medical system was replaced by a more holistic approach, what is often referred to as marginal gains. Every little detail was obsessed over, with nutrition being one of the most important. Essentially that is the fuel that powers us, just as you wouldn’t put diesel into a state-of-the-art rocket.

It took a decade of on the ground experimentation to work out what worked best and as there was no evidence out there, we were at the cutting edge. I have to say, personally, I’ve tried everything, from gluten-free to ketone and vegan, but over the years I learnt what was best for me was to listen to my body. Normally if it craved something it meant it needed it; the trick then is to moderate that input. It may sound cliché, but every body and mind is different, and it’s only through trial and error that one learns what works best for your own.

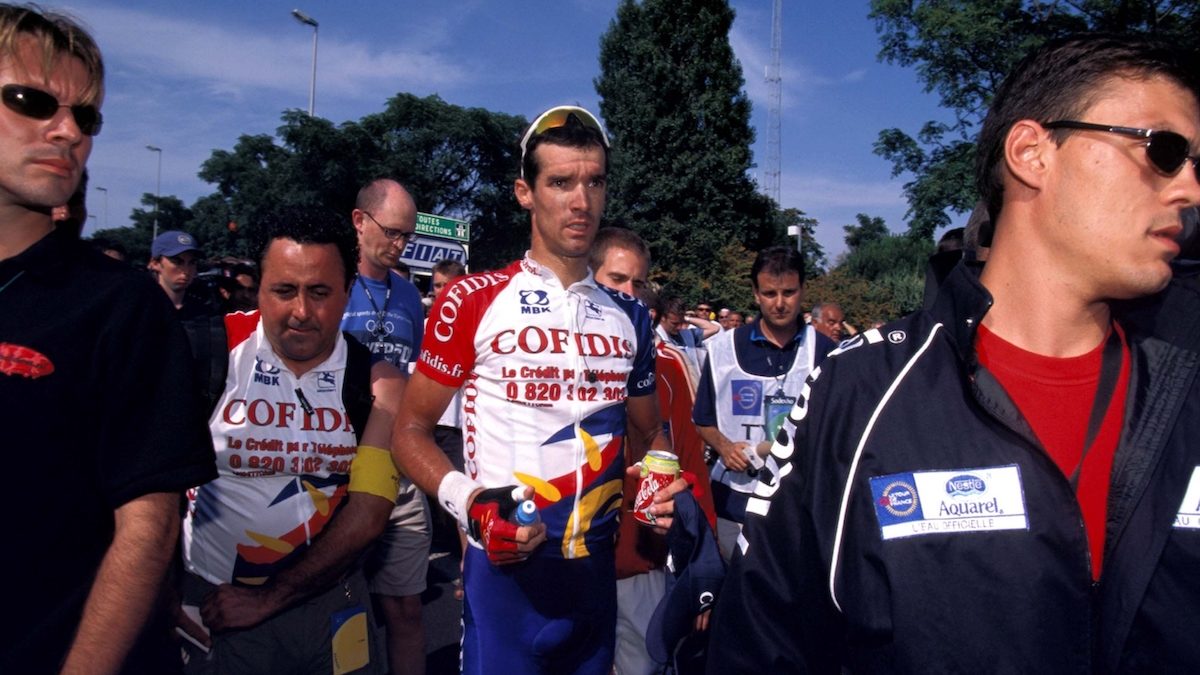

TOUR DE FRANCE 2002 / MILLAR DAVID / TDF / RONDE VAN FRANKRIJK / www.iso-sport.be

Adapting Your Nutrition To The Race Ahead

The bonkers things about professional cycling, is that there are so many different requirements when it comes to your nutrition. For example, in one year I became national champ in three different events – the 4km Individual Pursuit, Time Trial, and Road Race.

The 4km pursuit meant being able to go flat out on a velodrome for just over four minutes, while in the Time Trial you needed to ride point to point on an undulating circuit for an hour. Then in the Road Race you have to go as hard as you can for five hours on an open road against 200 other racers.

As you can imagine each requires completely different fuelling strategies in order to perform optimally. During the heaviest days of road racing we’d burn about 7000 calories, but they didn’t happen very often; if only in a one day Monument or the biggest mountain stages of a Grand Tour.

Managing your weight is everything to a professional cyclist though, as we’re totally dependent on maximising our power to weight ratio. ‘I am light. I am strong,’ as a mantra sums it up pretty well. It didn’t matter how strong you trained yourself to become, if you weren’t as light as you could be it meant nothing.

CHRONO DES NATIONS 2010 / LES HERBIERS / PHOTO: BRUNO BADE

Fuelling Yourself Through A Race

Although the pre-event fuelling won’t change too much – good old fashioned carb-loading never goes out of fashion – how you fuel in the race is often changing, depending on what’s available and what you’re planned energy expenditure is going to be.

When it comes to training, there has been a trend over the past decade to consume more fat and protein in training rides, as it conditions the body to be more efficient. Carbs are only used for super intense training or racing then, where your body is running rich and needs higher burning fuel. But, I’m quite off the back with what’s going on these days. The last five years have seen nutritional learning plateau, whereas my era was still in the learning curve.

The Biggest Nutritional Mistake Cyclists Make

The biggest mistake I see people making is simply not being prepared. For the majority of people common sense is enough to get you through the hardest of days. Yet it still blows my mind what I see some people do, either by not eating enough or trying something new on the big day they’ve been training for.

One very big rule of thumb is to never try something new on race day. Granted for many people they’re not racing, but if you want to get the best out of yourself then you need to respect those big physical challenges the same as a professional would prepare for any objective. We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.