Sleep Trackers: Are We Over-Analysing Our Shut-Eye?

We’re currently in a state of tracking overload. Calories are counted, every step documented, each heartbeat laid out before you in a slew of bar charts and figures. According to a YouGov poll in 2020, 27 percent of those surveyed own and currently use a smartwatch or wearable fitness band. And this tracking doesn’t just stop when we do.

As most fitness trackers continue tracking into our sleep we’ve also become obsessed with documenting what happens when our eyes shut.

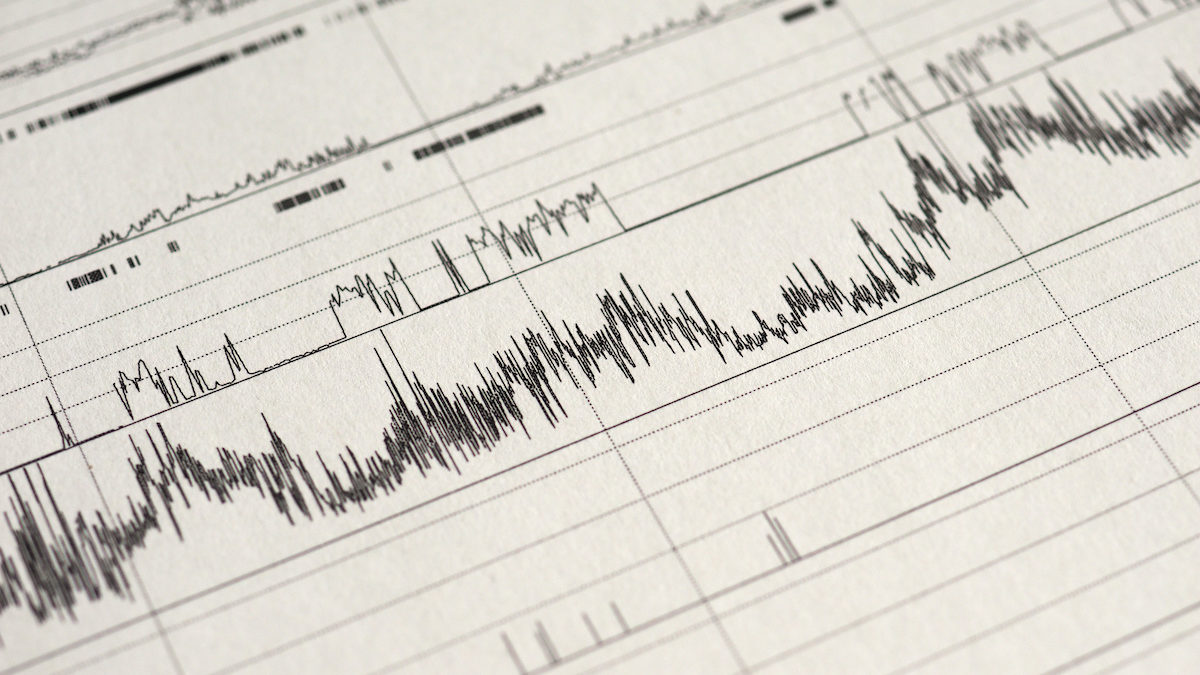

Trackers which measure heat rate can continue into the night, you see, and in return show you how long you’ve spent in each of the three stages of sleep — deep, REM and light — plus, of course, whenever we’re rudely awakened.

Some really smart watches can even monitor blood oxygen saturation, allowing the user to see when they might be suffering from breathing disturbances that are leaving them feeling fuddled in the morning.

“Initially the sleep tracking was something that I just saw as an ancillary accessory,” says Rory Cartwright, 27, who works in banking, and has become a regular sleep tracker since purchasing a Fitbit to measure his heart rate while working out.

“I think a lot of people just think of sleep as when they get into bed to when they get up in the morning, and what the tracker shows you is that you have to be in bed a lot earlier than you think. It’s nice to see your sleeping patterns over a period and have something that seems scientific to back up my groggy feelings as opposed to just wondering why you’re tired all the time.”

In The Name Of Science

And indeed science has been relatively thankful for all the added data. A study released in August 2021 by the University of Michigan was able to glean 130,000 days of data from 900 interns who continuously wore wrist-based sleep-tracking devices to collect motion and heart rate data.

This is where potential pitfalls might start to appear for those using sleep tracking outside of scientific, research-led surroundings though. Like calorie counting, we’re only guesstimating, with research from Yale University finding that compared to polysomnography tests – which experts use to diagnose sleep disorders – sleep trackers are only 78 percent accurate when identifying sleep versus wakefulness, a figure that drops to just 38 percent when estimating how long it took participants to fall asleep.

It’s important then to not put too much faith in what the trackers are telling us; but unfortunately, we do.

The Anxiety Of Tracking Every Sleeping Moment

Naikee Kohli works in business operations and originally bought his Whoop band to improve his sleep quality and see how heavy exercise and alcohol were impacting it. “I mostly just take note of when I get a particularly bad rating and see what I did correctly or incorrectly, but I do sometimes dread looking at the score when I know it is going to show poor recovery.”

Likewise, Cartwright has started to notice the impact a “bad score” has on his day. “Sometimes I’ll feel good in the morning, and the Fitbit will say I slept poorly and it will make me think I’m more tired than I actually feel. I’m putting more trust in this little thing on my wrist than on how I’m actually feeling.”

All this anxiety can be a massive hindrance to the thing that you’re trying to better, says Kathryn Pinkham, founder of The Insomnia Clinic, one of the UK’s only specialist insomnia services. “It could be you’re stressed about something and then you don’t sleep very well because you’ve got something on your mind. It could be that there’s another reason that causes the insomnia, but inevitably, when you’re not sleeping well you will start to feel anxious about the lack of sleep. So then it maintains it. It’s either the trigger or it maintains it.

“The more anxious we become about sleep, the more adrenaline we produce, the more fight or flight or negative thinking styles are going to be there.”

Pinkham has worked with a number of patients using sleep trackers and has seen similar mood changes depending on results.

“In the morning you’ll check it, and if it tells you that you didn’t get enough deep sleep, that leads you to feel more tired or fed up or negative of your sleep. You then might go on to cancel the gym or a social occasion because you were told you didn’t get enough sleep and you’re going to feel too tired, but that’s how the cycle of insomnia begins. We start changing things, we do less, we focus more on sleep. The sleep problem gets worse, and that’s how the problem is exacerbated.

“My advice is always to just carry on with your day, however badly you slept last night. Get up early and keep going because actually being over-vigilant about your sleep will make it worse the next night.”

Refocusing On The Treatment

This leads us to Pinkham’s main message: a need to refocus on the treatment. “You already know if you don’t sleep well. People with insomnia are aware of that. They don’t need a device to tell them. I’m an insomnia expert and I don’t know what stages of sleep I’m going through and how much deep sleep and how much REM. We can’t micromanage it anyway.

“So I guess my question to people usually is, how is that helping you to have all that information? I suppose the thing is the treatment is less of a product, whereas trackers are a piece of tech, and that’s quite attractive. You’re going to get the answers, but it’s just information. It’s okay to know it, but make sure that you’ve also got some way of treating or dealing with whatever information you’re about to find out.”

In the case of those suffering from insomnia, the main treatment for poor sleep is CBT or cognitive behavioural therapy, which teaches the patient to recognize and change beliefs that are affecting their ability to sleep. Pinkham also encourages people to just use a sleep diary instead of a tracker, and estimate their sleep as such.

“It’s just a piece of paper and you’re estimating how long you think it took for you to fall asleep, how long you were awake in the night and what time you get up,” says Pinkham. “The reason we do that is because once we’ve got a week’s worth of days, we can say, ‘look, you’re in bed for about eight hours, but you’re only getting about six hours of sleep.’ Based on that, we’re going to start the insomnia programme and start altering your sleep window to get better sleep.

“Really that’s all the information we need. I think we can usually guess if it took us longer than half an hour to fall asleep, and that’s sort of what we would need to know.”

So, while this analogue method might jar with all the tech presented to us, it shows that throwing all your Fitbits at the problem isn’t necessarily the answer. Certainly, in the case of sleep, it could all be doing us a lot more harm than good.