Lessons To Learn From Sustainability Past

Despite the current emphasis on carbon emissions, melting ice caps and fluctuating seasons, climate change and sustainability are not modern issues. Far from it, in fact. For several hundred years, communities around the world have been grappling with substantial ecological shifts — some man-made, others natural — and the impact that these changes can bring to daily life.

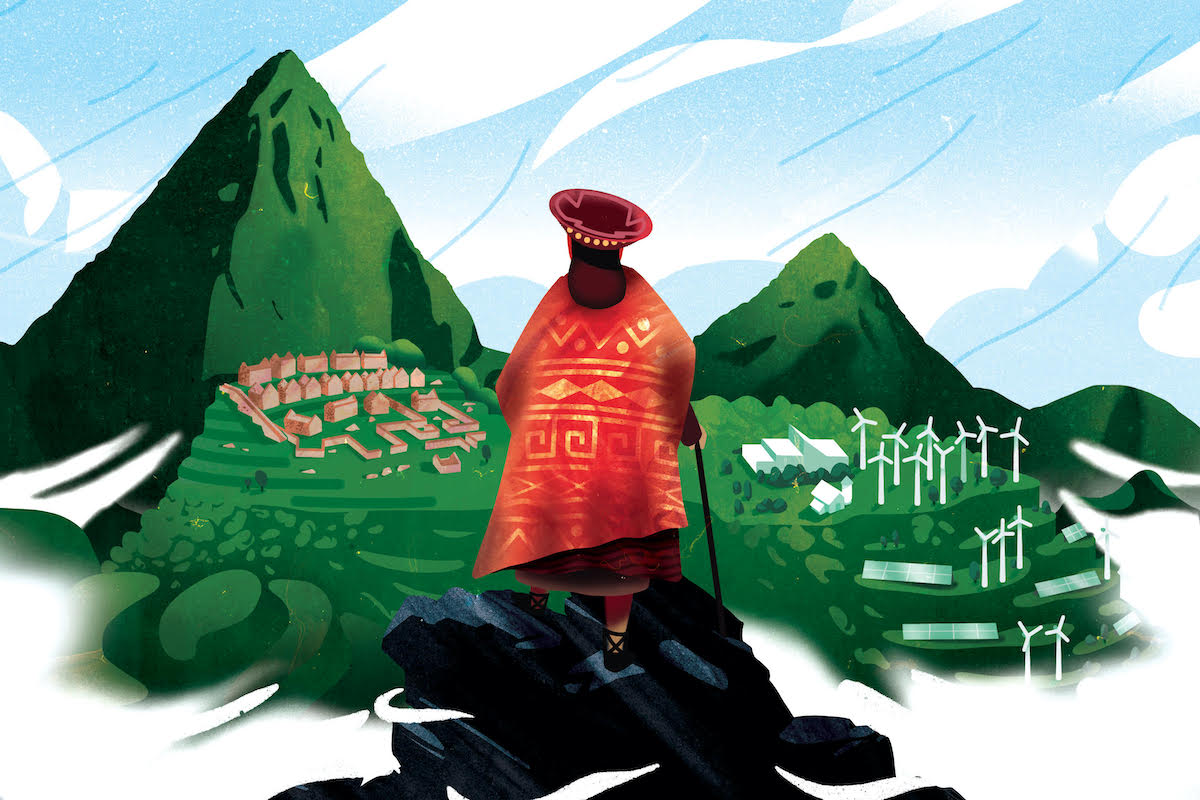

British archaeologists suggest, for example, that the Incas moved higher into the Andes mountains to avoid a 400-year warm spell in South America and to establish new farmlands and sustainable communities away from the changing environment. One such settlement was Machu Picchu. Fast forward to May 2021, some 600 years later, when it was announced that the UNESCO World Heritage Site was to become the first carbon-neutral wonder of the world.

By planting a million trees around the city and utilising the power of the Urubamba river to support a hydroelectric plant, the Peruvian government plans to completely eliminate emissions in the sky-high city by 2050. It’s a welcome step forward and one that has kept Machu Picchu out of UNESCO’s list of unsustainable and ‘in-danger’ sites, which includes Sumatra’s tropical rainforest, and Mount Nimba, on the borders of Guinea, Liberia and Côte d’Ivoire.

Looking across the Pacific Ocean to New Zealand, the Māori concept of Kaitiakitanga — a form of environmental management involving guardianship and care of the natural world — was officially recognised as legislation in 1992, honouring the “immutable and inseparable” connection between the human race and the world we live in. Like Peru, New Zealand is using its societal ties to the environment as a means to ensure longevity and encourage sustainability, so what else can those currently living in the ‘Anthropocene Age’ learn from these efforts in early modernity?

Just like the Incas moving away from rising temperatures, modern society is constantly unearthing ways to live a more sustainable lifestyle in a changing environment. Unfortunately, the urgency, with some even arguing we’re 250 years deep into an “unsustainable” way of life , shows no signs of abating. Simply put, the world is changing and we must change with it.

The data proves it too. As Jeremy L. Caradonna shares in Sustainability: A History, mentions of the word “sustainable” or “sustainability” within literature increased from almost zero to 5000 from the mid-1980s to the aughts. Similarly, there are now dozens of emerging occupations — from scientists to engineers and government officials to activists — who fall under the umbrella of “sustainists”, tasked with finding new ways to tackle an issue that is now centuries old.

“Most of the world’s human societies were ‘sustainable’ prior to the modern era,” Caradonna explains to Form in a separate interview. “Any culture that was able to live and flourish within its biophysical limits for long periods of time was, by definition, sustainable…one notable example that springs to mind are the pre-contact societies of Amazonia, where our understanding of pre-modern life and ecosystem cultivation has undergone a complete revolution in recent years.”

“We now know that Amazonia was densely populated and that native peoples cultivated the forest with over 100 domesticated plant species. They also built nutrient-rich soils, called Terra Preta, using biochar, mulches, composts, and other nutrient-rich inputs,” he says. “This sustainable form of polyculture lasted for at least 9000 years before the Spanish showed up with germs, guns and metal tools.”

Amazonia, Caradonna believes, “was a model of sustainability”, as it met several standards that made it a sustainable society. “Any society that managed to increase the fertility of its soils over time is the true measuring stick of sustainability.”

Perhaps, then, today’s sustainists — or, in fact, anyone looking to make noticeable change — can look to past methods of sustainability like that of the Amazonians. Another relevant example was Nachhaltigkeit, which, Caradonna writes in Sustainability, was originally “the practice of harvesting timber continuously from the same forest.” Despite its European roots, sustained yield forestry was found “in Japan, around other parts of Asia, and on colonial islands in both the West and East Indies.”

A German term which now directly translates to ‘sustainability’ itself, early eighteenth century Nachhaltigkeit was just “one indication of an incipient awareness about the value of living within biophysical limits and the need to counteract resource overconsumption.”

In Britain, a very similar situation had already unfolded in the 1600s during the English Civil War. In Sylva, writer John Evelyn “lamented that Britain’s forests had been ‘exhausted’ by decades of intensive shipbuilding,” Dr Tess Somervell, a Lecturer in English at Worcester College, explains. “Evelyn argued that trees were both necessary to the wealth and security of the nation, and beautiful and valuable in their own right.”

Evelyn’s readers were called upon to “take all imaginable care for the preservation and improvement of this precious material” and, such was the power of the message, Charles II ordered an enormous tree-planting campaign to create a more sustainable model for resources in war. 344 years later in 2008, the King’s descendent Prince Charles made a plea to world leaders to adopt a similar approach, saying that “We’d be crazy to ignore, apart from everything else, all the scientific advice and information that’s coming out.”

Another fathomable driving force for change was Europe’s industrial revolution in the late 1700s and early 1800s. The shift toward factory-produced goods “necessitated sustainability efforts”, Caradonna explains, “in the same way that the existence of war came before any peace movements.”

At a time when there were only one billion people on the planet, there’s a reason this issue sounds familiar in a modern context: because earth’s population has grown exponentially and so too has our consumption. “Only a society that’s living beyond its means would even think to create a sustainability movement. That’s exactly what happened in Europe. Sustainability was a reaction to overconsumption.”

“From the very beginning of the industrial revolution people worried about potential effects on the environment from pollution, deforestation, and industrialised agriculture,” says Somervell. Much of this critique came in the form of Romantic poets, she explains, such as Anna Seward, who wrote that the “black sulphureous smoke” of the factories was “like funeral crape” polluting Britain’s green spaces. “What literature could do was foster a kind of anti-industrial aesthetic – creating the idea that large-scale mechanised industry is ugly – which is a powerful idea that environmentalists still draw on today.”

All of which means there’s far more to sustainability — especially at a societal level — than buying beeswax paper (which, ironically, has been in use since the 1900s and can be traced back to the Egyptians) or bringing metal straws with you every time you leave home.

These, of course, have merit, but as Caradonna enthuses, be sure to “…live within your means. Treat the natural world as sacred. Increase the fertility of soils over time. Increase the biodiversity of your plants. Don’t over-harvest or commodify the natural world and use polycultures, aquaculture, and agro-forestry” to help preserve the only planet we can call home.

“Although we can never return to a pre-industrial world, we can learn a lot from history about how to live less destructively,” agrees Somervell. “It’s instructive to see how past generations have responded to the realisation that natural resources are not inexhaustible, and that we need to moderate our behaviour towards the environment if we hope to survive.”

Illustration by Thomas Pullin.

As a certified B Corporation, Form is committed to using business as a force for good. Learn more about the sustainable measures we’ve implemented in our product range.