An Introductory Guide to Carb Cycling and How to Tailor the Method to Your Goals

Carb cycling is a relatively new term, one adding to an area where there is already a great deal of interest. Over the last decade or more, the role of dietary carbohydrates has been the subject of fierce debate you see. This has led to a mainstream demonization of carbohydrate as a cause of many Westernised ills (specifically obesity and diabetes).

The result is a binary view of carbohydrate in the diet, from carbohydrates contributing the bulk of energy as staple foods in many national healthy eating guidelines versus advocates of low (or often very low) carbohydrate diets such as the ketogenic diet.

This ‘all or nothing’ argument is not only unproductive in terms of misinterpreting and misleading the science, but practically unhelpful. It is becoming clear that, for most of us, and in many circumstances, carbohydrate fulfils a key role in the diet, yet for most people, reducing or removing carbohydrate altogether may be beneficial at certain times or under certain circumstances.

What is carb cycling?

Carb cycling is a relatively new term that describes a strategy where an individual ‘cycles’ between periods of higher carb intake and periods of lower carb intake. This is not really describing anything new as such, as some people have been doing this, possibly inadvertently, for decades. However, the modern term carb cycling often reflects the motivation and rationale to this tailored approach to feeding carbohydrate. The rationale to carbohydrate cycling can be one or more of the following:

- To tailor the carbohydrate intake to the need/use of carbohydrate by the body (e.g. for exercise)

- To get the metabolic benefits of low carbohydrate, without removing carbohydrate altogether

- To tailor the carbohydrate intake to an individual’s tolerance of carbohydrate, possibly to improve their overall tolerance.

Rationale 1: To tailor the carbohydrate intake to the need/use of carbohydrate by the body (e.g. for exercise)

This is probably the most established way of carb cycling and is very much aligned to the evidence around performance nutrition. During exercise the predominant fuel used is carbohydrate, and that prolonged or high intensity exercise is synonymous with you depleting your muscle and liver glycogen stores of carbohydrate.

Hence conventional performance nutrition is very much focussed on strategies around fuelling up with carbohydrate before, during and, or after exercise. In its crudest sense, this type of carb cycling advocates that on a day when you exercise your carbohydrate should be higher, and on a rest day it should be lower. So, you can eat carbs when you need to burn carbs.

This type of carb cycling can be refined further by the specific timing of carbohydrate around exercise. For example, incorporating ‘carb loading’ prior to a competition, may involve several meals, or even days, of higher carb intake. Similarly, feeding higher carbs in the recovery period may also be advantageous to restore muscle glycogen before the next session/event. But we can be even more precise than this.

Depending on the nature of the exercise and the goals of the individual, we may want to time the carbohydrate differently, or not feed carbs at all. This brings in the idea of ‘training low’, which involves deliberately exercising with low carbohydrate stores (and/or no carbohydrate feeding) to amplify the cell signalling that drives adaptations in the muscle, and increasing endurance capacity through improved fat oxidation as a result. This ‘training low’ philosophy translates into different carb strategies befitting to the nature and periodisation of training (see macro/micro carb cycling later in the article).

Rationale 2: To get the metabolic benefits of low carbohydrate, without removing carbohydrate altogether

The proposed benefits of low/very low carbohydrate diets have been well documented in the literature and specifically aimed around the carbohydrate:insulin model of obesity and diabetes. There is clear evidence of their effectiveness as a means of creating weight loss, body composition change, and improvements in markers of insulin resistance (for more information you can read my keto diet series here).

However, there are some potentially practical problems associated with these types of diets, not more so the fact that for many people restricting carbohydrates is not necessarily sustainable or desirable long term. In addition, there may also be some issue of rebound carbohydrate intolerance should you reintroduce carbohydrates too abruptly after a long-term adaptation to a low carb diets.

So, adopting a carb cycling strategy could, theoretically, give you the best of both worlds, however the evidence for this is not necessarily to be found in studies looking at low carb diets particularly. These studies mainly look at short to medium term effects of transitioning on to a low or very low carbohydrate diet. Some study designs are of controlled crossover design which allow some examination of this transition, but very few look at the impact of transitioning off these diets (i.e. reintroducing the carbohydrate).

More useful insight can be gained through looking at studies on intermittent fasting (IF), as by design the “fast” in IF interventions is, by association, a period of carbohydrate restriction too. These studies (including my own), have shown that although you may have some temporally elevated glycaemia in reintroducing carbohydrate, the cumulative effect of repeated cycles leads to no detrimental effects on glucose tolerance, with possible overall improvements in your metabolic management of carbohydrate and lipid.

Marrying the known effects of low carbohydrate diets and the metabolic benefits of intermittent fasting suggests carb cycling could be as novel and impactful an intervention, but with less severe dietary restriction. This ‘intermittent carb restriction’ approach is indeed an avenue I am exploring in my work at the University of Surrey.

Rationale 3: To tailor the carbohydrate intake to an individual’s tolerance of carbohydrate, possibly to improve tolerance overall.

A third rationale for carb cycling links to growing interest around personalised nutrition. Specifically, it has been suggested that the positive impact of carbohydrate restriction, on outcomes such as weight loss, body composition and metabolic changes is a product of baseline carbohydrate tolerance.

In other words, those with glucose intolerance, or some insulin resistance to start with benefit the most from carbohydrate restricted diets. This makes perfect sense, given that you are removing or reducing the very thing they are potentially struggling to cope with. This has fuelled interest in the application of carb restricted diets in the management of diabetes.

Indeed, insulin dependent type 1 diabetics already routinely adjust carb intake and insulin administration, whether that be manually or by a glucose insulin pump that monitors blood glucose and automatically adjusts insulin administration. Recent approaches to management of type 2 diabetes have also seen diabetes remission following a very low calorie diet (which is also by association very low carbohydrate).

Given the points covered in rationale 2, it is conceivable that carb cycling can also benefit those with type 2 diabetes, independent of weight loss. Carb cycling could be a very useful strategy to improve metabolic tolerance, especially given a minority of type 1 diabetics, and not all type 2 diabetics are not overweight or obese.

This carb cycling could also be very nuanced to include meal timing and composition, taking advantage of known changes in glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity because of circadian rhythm. For example, timing carbohydrate meals to earlier in the day when insulin sensitivity is highest or entraining better tolerance of glucose later in the day by manipulating carbohydrate patterning across the day. All of these are ways in which carb cycling can be used as part of a more personalised nutrition approach.

6 Carb Cycling Strategies To Tailor To Your Needs

Given the different rationale outlined, carb cycling could be applied in different ways, as such, the exact carb cycling strategy will depend on what you are trying to do. For ease of interpretation, you can categorise these strategies into macro cycles and micro cycles, both of which could actually be employed in combination.

Macro Cycles

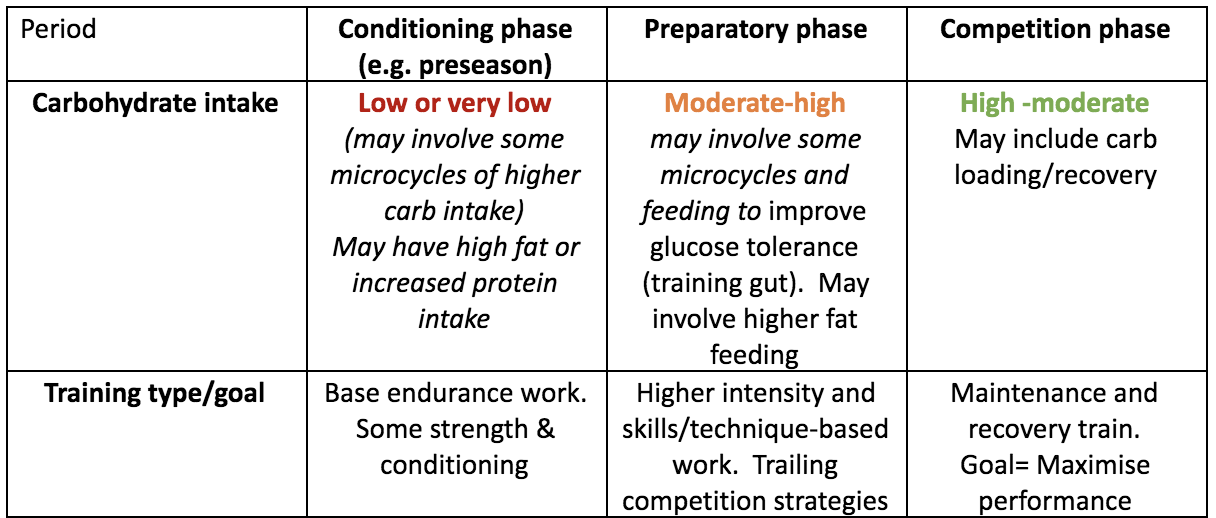

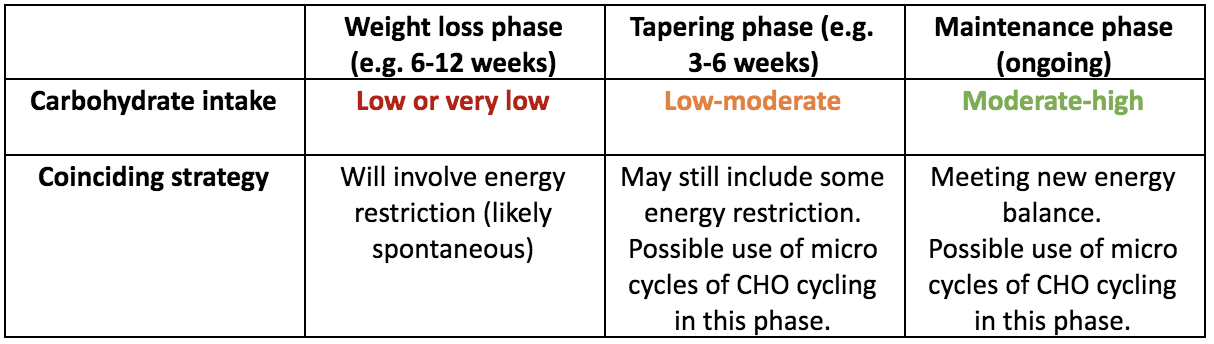

A macro cycle relates to carb cycling over relatively long periods, spanning weeks or months. This may include prolonged periods of low carb eating, possibly very low carb or ketogenic levels of carbohydrate intake per day (e.g. less than 100g per day), transitioning into periods of moderate to higher carbohydrate intake. This approach can potentially be used to achieve a long term goal such as weight loss, or coincide with a periodisation of training. Examples of this approaches are shown in figure 1.

Periods of training for many athletes often involve phases that could benefit from lower carbohydrate intake, by way of helping adaptations to endurance-based training such as increased capacity for fat oxidation. Note that some ultra endurance athletes may not actually transition much out of the conditioning phase at all.

As previously mentioned, for non-athletes low carb diets are shown to be a successful strategy for weight loss, possibly aided by the likely spontaneous reduction in energy (calorie) intake that often accompanies it. As a macro cycle, reintroducing carbohydrate could be phased in as part of weight maintenance.

Figure 1: Macro cycles of carb cycling (very low = less than 100g per day, high = over 50% daily dietary energy)

Example 1: “macro” carb cycling across a periodisation of training

Example 2: “macro” Carb cycling for weight loss

Micro Cycles

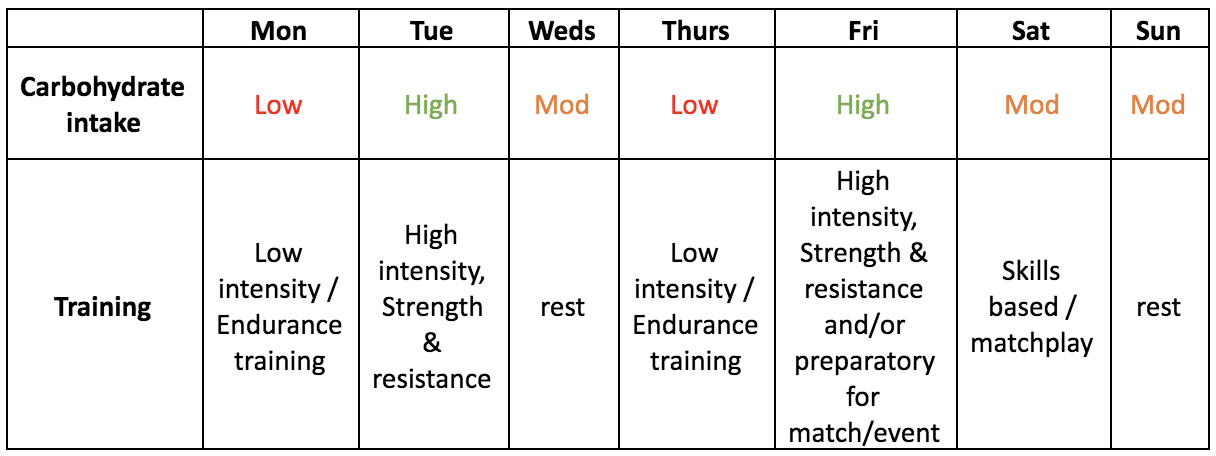

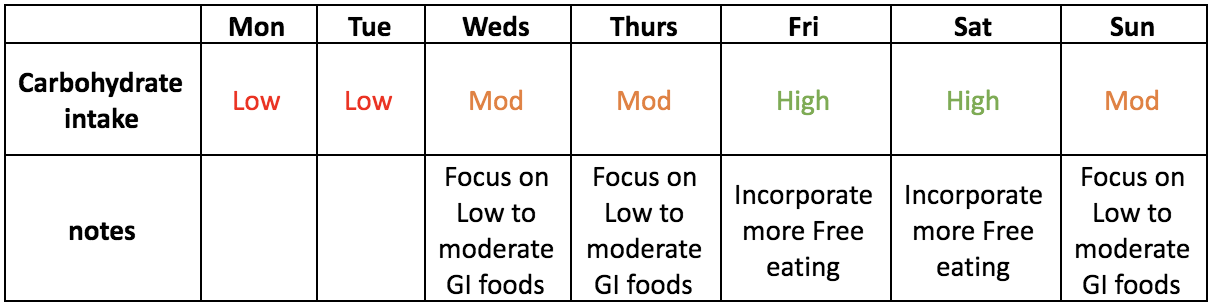

A micro cycle relates to carb cycling over relatively short periods, spanning days in the week or even within each 24 hour period. Carb cycling has been termed crudely by some advocates to describe high carb days or low carb days, but this is a simplistic approach that does not account for the nuances previously described. Furthermore, you will see that even within macro cycles (figure 1), micro cycles can also be employed to further tailor carbohydrate feeding to achieve certain goals.

To try to illustrate the use of micro cycles I have given some examples of how this may manifest in figure 2. During the periodisation of training, it is likely that both macro and micro cycles may need to be employed as the nature of the exercise training changes.

Figure 2: Micro cycles of carb cycling (very low = <100g per day, high = >50% dietary energy)

Example 1: weekly “micro” carb cycling within a periodisation of training

Example 2: weekly “micro” carb cycling for weight tapering/maintenance (a 5:2 approach)

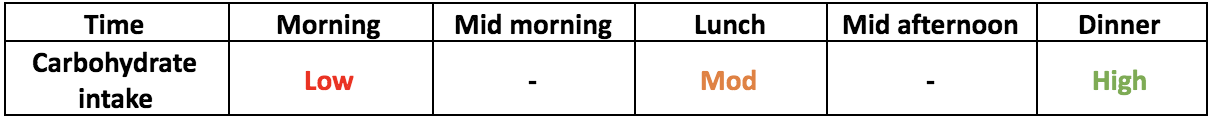

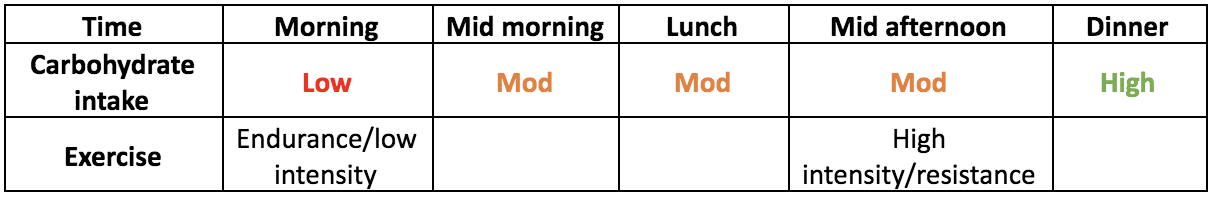

Example 3: 24 hour “micro” carb cycling.

No Exercise

Note: this can equally be flipped to high carb breakfast through to low carb dinner. Snacks/drinks between meals are not required

In combination with exercise

You can see from these examples that the carb cycling approach can be incredibly tailored to the individual, their goals, exercise and lifestyle. This nuanced view of carb cycling clearly demonstrates the great potential it has in combining the known metabolic effect of carbohydrate manipulation, the behavioural impact of carbohydrate restriction and the links between carbohydrate feeding, and exercise performance and recovery.

However, this still does not fully consider other influences such as chronobiology, gender differences, metabolic state (e.g. diabetes and obesity) and ageing. Nor does it consider other macronutrients such as protein and fat, or indeed the micronutrients in the diet.

A Move Away From ‘Low Carbs Vs. High Carbs’

Carb cycling encompasses a range of potential approaches that translate known benefits of carbohydrate manipulation for health and/or performance. It also aligns to our emerging appreciation of the benefits of other strategies such as intermittent fasting and chrononutrition.

This move away from the bipolar, black and white view, of low carb versus high carb is very welcome, but, serves to illustrate the complexities of applying personalised nutrition even on this basic level. Suffice to say we need to research this in well controlled studies, something that I am leading work in my role as head of nutrition at University of Surrey.